Catherine Mason is an Australian-born art historian and author specializing in digital and computer art. Mason’s career spans over 30 years, during which she has worked in commercial galleries, public-sector arts organizations, adult education, exhibition organization, and academic research. Her expertise in the history of computer and digital art began in 2002 when she joined an Arts & Humanities Research Council research project at Birkbeck College.

The following text is an authorised reproduction of the essay by Catherine Mason as it appeared in the "Feeding Consciousness" exhibition catalogue produced by The Halcyon Gallery in 2023.

AS IF STIRRED BY MAGIC

"The visible world became like a tapestry blown and stirred by winds behind it.…and I, with my imagination more and more drawn to adore an ideal nature, was tending to that vital contact in which what at first was apprehended in fantasy would become the most real of all things."

George William Russell (known as AE), “Retrospect” in The Candle of Vision, 1918

Bright, colour-saturated butterflies flit across our field of vision, they look real and artificial at the same time. How they arrived seems a mystery, yet magically, with a sweep of our hand, they move, settle, and re-arrange themselves in random formations, as if driven by invisible winds. They loop and weave themselves into our experience of reality. It feels very immediate and very personal. Dominic Harris knows how to harness the magical, the fantastical and the sublime, igniting our imagination and offering a glimpse of the unknowable. The butterflies in Harris’s on-going Metamorphosis series are hand-painted by the artist – some are existing species, others artistic invention. The use of digital technology gives Harris the means to produce movement and, most seductively – interaction, thus creating an immediacy with the viewer that no ordinary still life could. His digitally driven moving image works allow for infinite possibilities, the interactivity means our experience of them is never the same. Harris is clearly a storyteller, yet his is not a prescriptive narrative, he sets a stage and leaves us to enjoy the ride.

It may be a truism that art makes us see the world differently but let us consider the impact that an interactive multi-disciplinary art can have. Could it point to the magic, the strangeness in the world that perhaps alludes us in the day to day? An interruption to the quotidian that breaks us out of ennui by playing with a sense of time, objectivity and even self. An opportunity to access the weird, the unusual. Weirdness exists in the space between fact and fiction and non-fiction; it blurs the lines between the imagined and the observed. It can be overwhelming and transformative or bewildering and entertaining. Freed from a limiting linear narrative, an exploration of the strange in art can inspire new routes for vitality, contemplation and experience. [i]

Harris’s unique aesthetic continues the tradition of Romanticism and concepts of the sublime that have intrigued artists since the late 1700s. Drawing on these concepts of the different, the otherworldly, the awesome, his work evokes the wonder of the natural world, the grandeur of nature or indeed the strangeness of contemporary life. There is magic and beauty in his vision.The sublime is associated with the extraordinary and the exceptional, those rare occurrences of elation and exaltation, that are part of the experience of being human. It represents a taking to the limits, to the point at which fixities begin to fragment.[ii] In this way it disrupts stable coordinates of time and space. For philosopher Edmund Burke, writing in the mid-18th century, so vast and unknowable was this life experience that it was tinged with a thrilling degree of almost horrible astonishment: “The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature . . . is Astonishment; and astonishment is that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror. In this case the mind is so entirely filled with its object, that it cannot entertain any other.”[iii] This sublime is ennobling, in that it has the power to transform the self.

Romantically inclined artists have always known how to connect with the allure of the magical and the inexplicable. The painters and writers of the original Romanticism movement placed emphasis on the individual’s intense emotion as being an essential part of the artistic experience and artists and poets were seen as heroic figures with special access to these emotions. No longer distracted by previous social conventions, this was an art that could be free to express humanity’s joy in nature. Awe, wonder and even terror were considered valid responses.

Caspar David Friedrich was an early specialist in depicting scenes that instil awe and induce amazement in the viewer. In Wanderer above the Sea of Fog the figure with his back to us becomes us, we are both viewer and participant, as nature challenges our capacity to understand and fills us with wonder. We follow Friedrich’s Wanderer into his psychological experience of the vast and unknowableness of the natural landscape spread out seemingly unending before him. Humanity is but a small part of this grand universe and yet we are indelibly connected and inextricably bound up with it.

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1817 (Kunsthalle Hamburg) Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Huge shelving slabs of sea ice confront us in Friedrich’s The Sea of Ice. A shipwreck is just visible, pressed among the vast sheets of overlapping ice that fill the entire picture plane; it is clear that humankind and their explorations are ultimately insignificant in the face of nature. The strangeness of the unknown, the horror and pleasure of the sublime are here combined.

. Caspar David Friedrich The Sea of Ice, 1823–24 (Kunsthalle Hamburg) Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

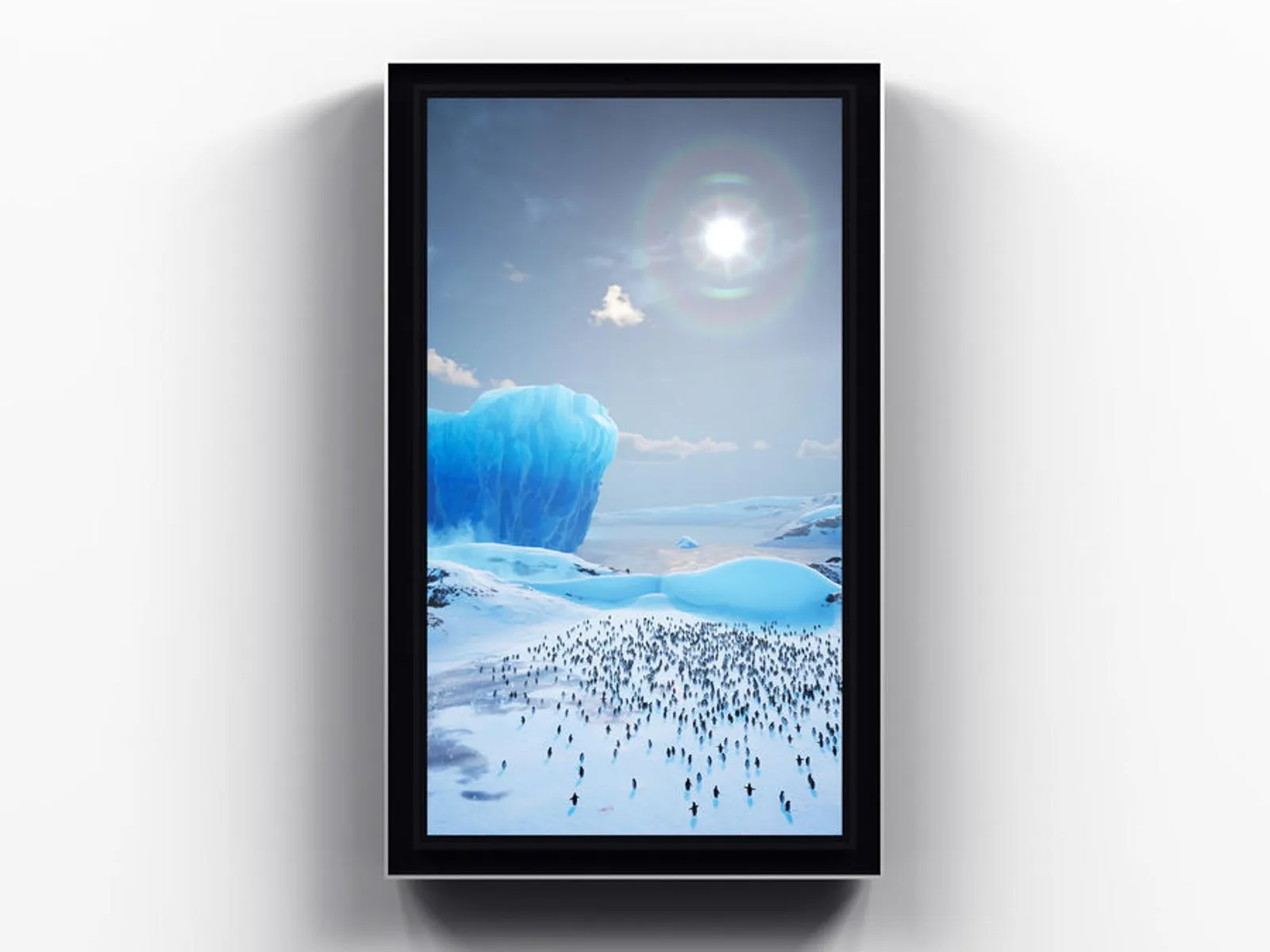

Harris’s Endurance (2022) continues this exploration of the sublime through snow covered polar landscapes. Set across four-screens, this is an exploration of fragility based on the story of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s expedition and the lost ship, trapped in pack ice. When Shackleton first sailed to the Antarctic it was a previously unexplored world. Today, the polar regions have been much explored; 107 years after sinking, the wreck of Endurance was discovered in 2022. However, these environments are increasingly fragile and their inhabitants at risk due to climate change.

Dominic Harris, Endurance, 2022.

In Harris’s interpretation we enter the landscape by touching the screen and, as we roam among penguins and polar bears, exploring, we can affect changes in the clouds and weather. We realise our impact on the fragile ecology. However, the digital system always returns to the original state of calm - nothing is ever irrevocably destroyed in Harris’s works. Allied to this piece is Arctic Souls (2022), focusing on three of the Arctic’s most vulnerable creatures. The high quality of Harris’s digital workmanship is immediately apparent in these beautifully detailed animals brought to life before our eyes. It is remarkable to realise that there is no photography involved; as in all of Harris’s art, the imagery is hand crafted with his own in-studio code – what Harris calls “the mathematical magic behind the scene.”[iv]

Britain has a long history of landscape painting that engages with evocation and manipulation of the symbolic: from the visionary poet and painter William Blake to JMW Turner’s emotive seascapes, to John Martin’s great spectacles. Blake’s was an art of imagination and his other-worldly vision, rich in symbols and self-invented mythology, has been seen as an expression of human spiritual existence. The Ancient of Daysshows Urizen, a demiurgic figure (originally from the Greek for craftsman or creator), as an artisan-like figure, responsible for fashioning and maintaining the physical universe. Here, Urizen holds a compass, drawing on traditional symbolism of God as the great architect of the universe.[v]

_British_Museum.jpg)

William Blake, The Ancient of Days, 1794. Frontispiece for book Europe: A Prophecy. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

John Martin created an art full of portents, judgments and visitations, founded in history, religion and legend. Martin’s landscapes, depicting storms, lightning bolts, gushing waters, towering rock formations and cavernous skies, expanded compositional elements from Turner, some fourteen years his senior. For example, Turner’s atmospheric swirling vortex of wind, hail and cloud in Snow Storm: Hannibal and his Army Crossing the Alps, (Tate, 1812) is used by Martin in The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum (Tate, 1822). Martin turns this into a vortex of volcanic eruption of fire and molten rock against a phantasmagoric sky. Turner understood that a high contrast of light and shade could be a metaphor for mood, feeling and ideas, not just an absence of dark. Martin’s landscapes used light to reflect the terror of the protagonists, their impending sense of loss and desolation to be averted through piety.

John Martin, The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum, 1822 (Tate) Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Martin’s vast oil paintings of dramatic subjects (this one is over eight feet across) were designed to fill the entire field of vision, to create an immersive viewing experience. The Destruction of Pompeii was the centrepiece of his one-man show at the Egyptian Hall, London in 1822, a place “where the loftiest of fine art shared common ground with freaks, curiosities and theatrical spectaculars.”[vi] Martin’s work was closer to the entertainment of contemporary panoramas and dioramas, than the staid traditions of the Royal Academy.

Martin was able to take advantage of the explosion of visual spectacles in the late Georgian and Regency world encouraged by Romantic poetry and novels. The panorama consisted of a large painted cloth, a French invention that arrived in London in 1789. Using artificial light, these often had physical, movable elements such as transparent screens to control the audience’s experience, creating a sense of depth. The diorama, a blend of stage scenery and panorama, provided an even more immersive experience. Patented by Louis Daguerre (later inventor of the earliest commercial form of photography), it first opened in London in 1823. Taking place within a darkened space, scenes were painted on both sides of a large translucent canvas, animated by the skilful use of artificial light - light was projected onto the picture surface for sunlit scenes and projected from backstage for moonshine subjects. The result was “the painting became the object of tunnel vision, with the pitch-blackness of the auditorium funnelling the audience’s attention towards the spectacle of light”[vii] and creating a progression of moods and feelings in the viewer. Some dioramas even had rotating viewing platforms that moved the seated audience from one scene to another. Martin also plays with time, as all stages of the volcanic catastrophe are compressed into one picture frame. These can be considered as precursors of digital art, and as close as could be to ‘moving image’ at the time - the gas light would play across the surface illuminating specific details of the painting in turn. Even without the light show, today, Martin’s cavernous skies glow brightly and appear almost backlit, like digital screens.

Harris’s art extends these traditions - his artworks are very experiential. He has spoken about the screen not being the edge of the artwork.[viii] This recalls the famous cinematographer Stanley Kubrick’s comments about the screen being a “magic medium”, one that “has such power that it can retain interest as it conveys emotions and moods that no other art form can hope to tackle.”[ix] Using a palette that is infused with technology offers Harris the ultimate interactivity, and thus an even greater degree of engagement with emotion. In this way an additional aspect, what might be considered a new ‘technological sublime’, comes into play.

Harris’s new works Monuments (2022) and Dioramas of the Divine (2022) sit within these traditions. In a beautiful example of the motion capture technique, Monuments presents three moving figures of Greek gods: Zeus, Atlas and Poseidon, each with their attribute. Soon we discover they are not the carved classical statues they at first appear, indeed we can interact with these figures. Harris explains, “They are ‘humanised’ – they suffer from boredom, for example. Atlas’s globe is actually very heavy. This makes them more relatable to us mere mortals.”[x] The landscapes these gods inhabit are shown alongside, across three screens, they are imagined worlds, a companion piece to the figures. With a move of the hand, we are in the realms of the gods, moving effortlessly through the skies, across mountains and under the seas (is that a glimpse of Atlantis, possibly?), all the while admiring the remarkable detail on these fantastical, magical scenes as the day fades to night at our whim. Disruption does occur, but there is always the sense of a happy ending just around the corner, as the moving image works reach homeostasis, nature settles back into balance and harmony.

Dominic Harris, Diorama of the Divine - Poseidon, 2023.

These pieces, like much of Harris’s art, have a meditative quality – they might be considered ‘slow art’. They invite us in, to lose ourselves in their rich detail, whilst firing the imagination. They are a welcome respite from the fast-paced, information overload that can characterise contemporary life. Art has always been inextricably bound up with technology. Using a set of skills and techniques, art is about making intangible ideas visible so that they exist as objects or events in the real world. Artists throughout time have always sought the ‘new’ and been excited to discover how far they could push the latest technologies to realise their ambitions. And when digital technology was first invented, artists were naturally early adopters, helping to shape the bourgeoning field of computer graphics by collaborating with scientists to create drawing programmes and software packages to fulfil their aesthetic aims.

It is clear that developments in digital and information communication technologies coming out of the massive impact of WWII both terrified and inspired artists. The impact of this new ‘machine age’ was considered from the 1950s onward. The artist Richard Hamilton, who had a broad vision of the arts unrestrained by limiting definitions, saw the relation between human and machine, as “a kind of union. The two act together like a single creature”, symbolised for him in the myth of the centaur, “a fusion of horse and rider into a new, composite creature.” This was important, Hamilton believed, because it “liberates a deeper, more fearsome human impulse. This new affiliation [of human and machine], evoking much that is heroic and much that is terrible, is with us [...] for all foreseeable time.” It was necessary, indeed crucial, to consider this new human-machine interrelationship, because, again in the words of Hamilton, there is “no other means of assimilating disruptive experience to the balanced fabric of thought and feeling.” [xi] In the following decades, the use of computing as an art method, material or tool became a means through which ambivalence towards such technology could be reconciled. A coming to terms with the origins of this digital technology, much of which was developed because of weapons research, whilst recognising the amazingly creative potential of machines.

In the artworld, this was centred around the relatively new post-war science of cybernetics, popularised in the late 1940s by Norbert Weiner. [xii] Cybernetics dealt with control and communication in living organisms and machines, including the communication within an observer and between the observer and their environment. This communication is fed back into the system, thus affecting the overall output. These theories helped to form a framework for art production in which artists could consider new technologies and their impact on life. Concepts of behaviour and process, media dexterity, interdependence and co-operation began to enter art. Art was seen as a system involving feedback between creator and audience, where process was an important part of the equation. The viewer contributes inputs that change the outcomes of the artwork.

Inspired by a positive ‘human machine interrelationship’, artists from the mid-1960s employed technological systems to extend the meaning and functionality of art. During this time art underwent a revolution - the definition of what art was or could be was questioned and the role of the artist reconsidered. This allowed for new methods and systems to come to the fore, including digital technology. Such methods and tools naturally appealed to those artists from an architectural, constructivist, or kinetic art background who were already thinking about art in a computational way and interested in the dynamic interplay of space and movement. Modern electronics enable simulation of living organisms.

One of the most noted pioneers of an art based on computer-mediated interaction was Roy Ascott who set his practice within a cybernetic perspective of the world. For him, the computer was not simply a new set of sophisticated tools, but a new vehicle of consciousness, of creativity and expression.[xiii] By considering art as a system, within a behaviourist framework, “the creative interplay of reason, passion and chance can take place.”[xiv]

Interest in all things cybernetic in Britain came together with the exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity, at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in the summer of 1968. This was the first comprehensive international exhibition in Britain devoted to exploring the relationship between new computing technology and the arts and featured collaborations between artists and scientists. It is still considered the benchmark ’computer art’ exhibition for its influence on subsequent generations as well as introducing the subject to a wider audience. The Computer Arts Society was founded in its wake, as a forum for discussion and exchange of ideas among like-minded practitioners who wished to explore further the relationship of humanity and technology through art.[xv]

Installation view of Cybernetic Serendipity at the ICA, London 1968. ©Cybernetic Serendipity

Harris’s art, rather than defining representation, or setting a fixed narrative, invites us in, and encourages opportunities for participation, moving art beyond that of mere object. In Ascott’s words, “to render what is invisible visible, to bring the virtual, the potential, the unseen, and unrealised into view.”[xvi] Through this, the role of the artist is increased, the possibility opens for an infinite number of stories to be told, and the meaning of art is expanded.

This is artwork engineered from the ground up. Harris has spoken about his excitement, “working on the cusp of what technology permits.”[xvii] First the ‘canvas’, so to speak, is defined and developed in parallel with the requirements of the art itself, unique to each piece. Harris draws on his own extensive expertise to design, prototype and build in-studio, his own electronics, hardware, frames and plinths, working with specialist companies to create bespoke when required. Everything is so meticulously crafted, and the highly sophisticated hardware appears so minimal, that we are almost unaware of it when viewing the art.

Two new works by Harris address our contemporary information communication society, with its excess of data and constant bombardment of imagery. Limitless (2023) uses a real-time feed from the Internet of the Financial Times Stock Exchange 100 Index (the ‘Footsie’) to track stock movements. This creates a visual landscape of data in gold. We can see the stocks in play at any given moment of the day, represented as blocks, together with the faces of the main protagonists from each company. The composition of this work is inspired by Harris’s study of the Biblical story of the Tower of Babel. Harris, with his architectural background, has enjoyed researching the numerous examples of the Tower in art history, and inventing new ways of depicting it visually to make it contemporarily relevant.

_-_Google_Art_Project_-_edited.jpg)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Tower of Babel, 1563 (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Feeding Consciousness (2023), although also related to the Babel story and Limitless, applies datasets and Artificial Intelligence code to art in a novel way. This large artwork commands an impressive sculptural presence, and its physicality is very important - this Babel actually exists in three dimensions. Using a live stream from the Internet, the top five trending topics on Google’s UK search engine are displayed as text on a Vestaboard, a split-flap mechanical sign which has a pleasing, old-school retro appeal. These searched-for subjects are then visualised on dozens of individual computers, magnificently fitted together, spiralling upwards in a tall tower like a modern Babel. (Again, all this kit is beautifully designed and produced, bespoke, to the artist’s own specification.) We see what the Country is talking about, and it is not necessarily that which is in the official news. This represents a departure for Harris in that it generates already existing imagery drawn from the web. It is interactive in a different way from his other works because it is the collective ‘we’ - the whole of the UK, searching the Internet at any particular time, who affect this work. And it is constantly changing as our attention span flits from one idea, one ‘click’ to another, all day and all night long.

Dominic Harris, Feeding Conciousness, 2023.

These artworks present stories that are unending - as long as the electricity remains connected, the digital medium facilitates continuous, never-repeating variations. However, unlike the original story of Babel, which ultimately failed as the people building it became too powerful in the face of God, in Harris’s works his natural optimism shines always through. He sets the scene in a non-judgemental and non-polemical way; it is left to the viewer to make up their own mind. As society navigates these post-secular times, caught in a global system of control and consumption, is this a salutary tale - has our technology become god-like? If humanity cannot work together in the face of our many challenges, will we ultimately fail? Once again, Harris’s art sparks our imagination and poses open-ended questions with no set answers.

In contemporary life we look to stories to make meaning amid the chaos. Today when AI image and text generators seem poised to replace the artist and poet, it is multi-disciplinary creatives like Harris who understand that artists can have a greatly amplified power by embracing the complex, real-time responses of an interactive art system. The viewer becomes a collaborator with the artist. This will ultimately keep art relevant and exciting. Harris connects with beauty to transform the destabilising influence of our now ubiquitous technology via the sublime (and a dollop of other-worldly magic), using the very technology that continues to shape our lives in profound ways. In this way, as Roy Ascott wrote over thirty years ago, we can hope to “glimpse the unseeable, to grasp the ineffable chaos of becoming, the secret order of disorder.” [xviii]

SOURCES

[i] Mark Pilkington, “How to Believe in Weird Things”, in Jamie Sutcliffe (Ed.), Magic (London: Whitechapel & Cambridge Mass.: MIT Press, 2021): 63-67

[ii] Simon Morley, “The Contemporary Sublime”, in Simon Morley (Ed.), The Sublime (London: Whitechapel & Cambridge Mass.: MIT Press, 2010): 12-21

[iii] Edmund Burke, “A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful”, 1757, in David Womersley (Ed.), Edmund Burke: A Philosophical Enquiry into the Sublime and the Beautiful (London: Penguin, 2004): 101

[iv] Dominic Harris, communication with author

[v] Stuart Peterfreund, William Blake in a Newtonian World: Essays on Literature as Art and Science (Univ. Oklahoma Press, 1998)

[vi] William Feaver, The Art of John Martin (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975): 55

[vii] Daguerre’s Diorama, Dead Media Archive, NYU Dept. of Media, Culture, and Communication: http://cultureandcommunication.org/deadmedia/index.php/Daguerre's_Diorama

[viii] Dominic Harris, communication with author

[ix] Stanley Kubrick, quoted by Peter Krausz, “Paths of Glory: The Abiding Legacy of the Cinema of Stanley Kubrick”, Screen Education (St Kilda, Vic.), 41 (2005): 18-23

[x] Dominic Harris, communication with author

[xi] Richard Hamilton and Lawrence Gowing, Man Machine and Motion (London: ICA, 1955) preface

[xii] Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics, or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine (Paris: Hermann & Cie, & Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1948)

[xiii] Roy Ascott, “The Construction of Change”, 1964, in Edward Shanken (Ed.) Telematic Embrace: Visionary Theories of Art, Technology, and Consciousness (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2003): 97-107

[xiv] Roy Ascott, “Behaviourables and Futuribles”, 1967, in Edward Shanken (Ed.) Telematic Embrace (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2003): 159

[xv] For more about this history see Catherine Mason, A Computer in the Art Room: The Origins of British Computer Arts 1950-1980 (Norfolk: JJG, 2008)

[xvi] Roy Ascott, “Beyond Time-Based Art”, 1990 in Edward Shanken (Ed.) Telematic Embrace (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2003): 231

[xvii] Dominic Harris, “A Conversation” in Dominic Harris: Imagine (London: Halcyon, 2019): 15-21

[xviii] Roy Ascott, “Is There Love in the Telematic Embrace?” Art Journal, vol. 49, no. 3 (Fall 1990): 246-7